About 20 notebooks are socked away in producer-director-writer Edward Zwick’s office in no particular order, full of odd magazine clippings and notes. During the pandemic he rooted through them and rewatched his work, looking for the nuggets and details that would become his memoir “Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions: My Fortysomething Years in Hollywood.”

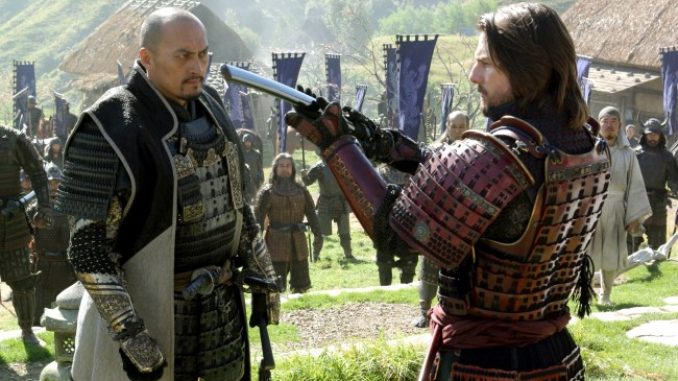

He chronicles a television career with longtime Bedford Falls partner Marshall Herskovitz — together they created “Thirtysomething,” “Once and Again,” and “My So-Called Life” — but much of the book tracks Zwick in the movie business, from Demi Moore and Rob Lowe in “About Last Night” in 1986, “Legends of the Fall” with Brad Pitt in 1994, “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise in 2003, “Blood DIamond” with Leonardo DiCaprio in 2006, and his last outing with Cruise, “Jack Reacher: Never Go Back” in 2016.

Zwick and I have talked many times over the years; we reconvened over Zoom to parse his book, which lays bare the highs and lows of his varied career.

Anne Thompson: What were you initially trying to achieve? When did you decide to take off the gloves?

Ed Zwick: There were these relationships that have meant an enormous amount to me. You’d spent hours together and rainy wet nights and fights and tears and love affairs. I was trying to try to find some meaning in what these years had been to me. When I started writing, I didn’t even know I was writing a book. You keep a file on your computer and I would write “b–k,” not to defy the literary gods by saying, actually, it was a book. To take a little pressure off myself.

But once I started getting into it, and I showed it to a couple of friends who are serious writers who I count on to tell me when I’m full of shit, they were encouraging. But they also said, “Look, what you would say to an actor, or to a writer at this point is, ‘Where are you? You’ve got to dig deeper.’” And once I began to do that, I had to make a determination. If I was going to be authentic about what my memories were, and what I believe happened, that earned me the right to be equally so about these people. It’s a case-by-case thing, but there seemed to be a dividing line for me. If people behaved badly, professionally, that felt to be fair game, but to embarrass someone, personally, for the sheer sake of dish seemed to be out of bounds. That might have been the line that I was drawing there.

The first time you had trouble with an actor on a movie was post-“Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” Matthew Broderick, who played the lead in the 1989 Civil War drama “Glory.” Not to mention his interfering mother.

I also went to great lengths, in that case and in a couple others, to try to be compassionate to understand what it is to be those people at that moment. He was 24 years old. He was surrounded by handlers and fluffers. And, his parent. That’s a lot of responsibility to put on the hands of a young actor, who’s not necessarily trained to be in that position and who then takes on the feeling and the anxiety of being responsible in this way. I tried to be mindful of what I would have been at 24. And at least showing some empathy, which at the same time, allowed me to be brutally honest.

You leaned on two partners in your life: your wife Liberty, who never bought into any Hollywood bullshit and kept you anchored to your family, and writer-producer Marshall Herskovitz, the co-founder of Bedford Falls.

Those were the terms that she set and I’ve had to abide by them, more or less. But Marshall and I realized we’re probably the longest-running partnership in Hollywood history. I know that Brian [Grazer] and Ron [Howard] came on like a year or two after us. We’ve done things separately, obviously, but we’ve done so much together. It’s the joy of being with someone who is your best pal and your brother, someone who you’ve had one long conversation for the entire time. You pick up without having to give the backstory or the exposition. And we’re still working.

I don’t think your memoir is like any other memoir that I’ve ever read. It lays bare how Hollywood actually works. How ugly it is.

I had an agenda: If only I could have had this book to read when I was starting out. There are going to be people who read this book because of the dish, and they’ve liked the movies, and they want to see the inside baseball. But my notion is there are going to be young filmmakers reading it, who are going to get something as to the rough-and-tumble of this process, and how failure plays a role and how to not think, “What’s going to happen if I get knocked down,” but when I get knocked down, how do you get up? How do you hold on to those things that were part of your dream, as everybody comes after you to tell you what your dream is supposed to be? The values of this place, and some of the toxicity of this place, is a strong force. It’s an entropy that you have to try to hold back.

You have a few mentors. One was Nina Foch at the AFI Conservatory.

She was extraordinary. She was an heir to a whole generation of Lee Strasberg and Uta Hagen and Stella Adler. She was confrontational, too. She didn’t take any shit from a presumptuous 22-year-old.

Sydney Pollack saw something in you and took you under his wing at TriStar.

I had done a thing for television called “Special Bulletin” [1983], and it got a lot of attention. I got a call from my agent saying Sydney Pollack would like to meet you because he’d seen it. He had just finished some movies, the TriStar studio had just been formed, and they’d hired Sydney to be a consultant. And Sydney said, “Come on over and have lunch.” He liked to cook in his own kitchen at lunch. He said, “So kid, you want to make movies? How about if we give you enough money to not have to work for six months, figure out what you need to pay your mortgage, and whatever, trying to think about what you might want to do, you can develop a couple of scripts, you could read a lot of scripts.” That led to to “About Last Night” and that was the game-changing moment. It was an investment in an artist by another artist who sensed his possibility.

I don’t believe that would ever happen now.

If anybody were to take the aggregate of the P&l of all my movies, and say, “Well, should we make this bet over 25 years?” The answer is, “Yeah, you should have.” But ever since that time, everything has become a one-off. The idea of investing in a laboratory where you bring in artists, and try to give them at least some grace to figure out what they want to do? I was the beneficiary of it.

They just don’t have those budgets any longer.

Not at all, and they want to give you a thing that is already finished. A thing is never really finished until you’ve gone through that process. “Glory” began as one movie and became another movie as it was made. They have to allow for a certain amount of improvisation, a certain amount of openness to what’s happening in the whole process.

Your movies, more than most, were organically grown. One of them was “Shakespeare in Love.” You ended up being the producer and on stage on Oscar night. But that was a torturous, unpleasant story with Harvey Weinstein. You developed it, you started it. You went to playwright Tom Stoppard and convinced him to do the rewrite.

I got to work with one of my idols in a delicious experience. I remember Hitchcock saying that you make the movie in prep, and by the time you’re shooting, it is already made. In that sense, I had already made the movie in my head. But I just never got to make it in the flesh, and I had to accept that disappointment. Heartbreak, as in life, is part of being in the movie business.

So you had already built sets, everything was going forward. And Julia Roberts crumbled.

There again, she was very young, there was a lot of pressure on her. She might have feared how she might have done in the role. But for whatever reason, she behaved badly. And [Universal chairman] Tom Pollock — whom I adored, who had been a supporter to me, he’d been my lawyer earlier on — chickened out, didn’t hold her feet to the flame. Whether there was another agenda there about other things with the star, or Mike Ovitz, or God knows who, it just went away. I had to say, “Okay, what now?” Had that not happened, I probably wouldn’t have gotten to make “Legends of the Fall.”

Pitt on “Legends of the Fall” was not easy, either. You called him “volatile” on set. What makes a movie star behave badly or act out?

You have to understand the anxiety, the level of fear and dread to be out there, fronting a movie. Actors have come into this more from a state of of hunger than from abundance. They’ve been shunted aside. They’ve been waiting to get into rooms; their whole life has been about reaching some perch and some purchase on a career. There’s this notion that the failure of a thing or the possible failure is a judgment, on their viability, on their bankability.

Listen, I have been extraordinarily anxious, never more so than when I’ve decided I’ve gotten the green light to do something and say, “What have I done? This isn’t going to work. And can I get out of this?” That’s a common thing that happens before the fact, before you actually realize that it’s one step at a time and figuring out the scenes and doing the work and you lose yourself in it, and then you relax a little bit. But before the fact, it’s not easy.

One of the actors that you had the most pleasurable experiences with, early in his career, was Denzel Washington. You got to see the the emergence of his talent in “Glory.”

It was like discovering a Ferrari. And all you have to do is just put your hand on the steering wheel and go like this, and the car will go screaming around the corner. His abilities to be present, and to be creative in a moment, so exceeded anybody I’d ever worked with. He saved my ass countless times with scenes that wouldn’t have worked. The number of times that I recall him saying to me, “I can act those words.” In other words, “Those words suck, don’t worry, I can do that.” And he didn’t mean that cruelly. His instincts about scripts, like Tom Cruise’s — there are reasons why these guys have careers with that kind of longevity. It’s not because of some play of light and shadow on their face. They are every bit as smart and as gifted as any director or any writer. They don’t necessarily have the same language, but you ignore their contribution at your peril.

Tom Cruise and “The Last Samurai,” another project you developed from scratch. I love that moment where you’re rewriting John Logan in your Colorado winter cabin.

John had written a wonderful first draft, but he was then not available to do more work. I made the mistake of actually submitting it to Tom. I’d met Tom years before several times. Graciously, he passed. I was disappointed and realized I had made a stupid rookie error, which is say, give something to somebody before it’s absolutely the best it could be.

I was sitting there in this room filled with weird things I’ve collected over the years. Some of it was from “Legends of the Fall,” which was the same period of the late 19th century. There were journals from a cavalry officer at that time and those officers who’d gone to West Point were not just taught to wage war, but they were taught rhetoric. There was this voice in these journals, this very spare, austere description of events, that I said, “Oh, God, what if I could juxtapose those against the passion that was happening internally in him, that would be a way to portray a character to see him go into a place he never imagined that he would emotionally.”

I rewrote the script in two weeks. I locked myself in there for hours and hours and hours. I walked back into [Warner production chief] Lorenzo di Bonaventura’s office, put the script on his desk, and said, “Here, I’ve rewritten it, you don’t have to pay me. What I want you to do is get this so that we can show this to Tom Cruise again.” He said, “Okay.” It is so rare for an actor to turn down something and then read it again.

Why do you think Cruise did?

It took away the objective veneer and the presentational part and found the inner life, which is always the thing that an actor’s looking for, anyway.

This was your chance to work on a studio movie with a major movie star where they just said, “Go ahead, do whatever.”

I was unprepared. I always fought my way through budgets. Warner Brothers said, “Here’s the money. Go to Japan. Find experts. Scout.” New Zealand is an island that looks like Japan; Japan doesn’t have that kind of terrain available because of the population. Suddenly we had a movie that was on three continents. I suddenly realized how sometimes these things become runaway trains. It was fortunate that I had done so much, shooting television series and often with my own money at risk, that I knew how to stretch a dollar. But I cannot begin to talk about the logistics of getting 700 Japanese fighters to New Zealand with translators and cooks and medics, not to mention the Spanish riders coming in six months early to find young horses who are willing to fall down. Ironically, one of the problems often is having to put the reins on everybody’s department who looks upon this as their moment to do their absolute best work. It becomes a movie about tatami or weapons, as opposed to the story.

You confessed your anxieties to Tom Cruise at one point. What happened?

At first I thought, “Oh God, he doesn’t want to hear it.” I realized later he had been in this situation so many times before. He wanted me to be that person who he could count on, who had these things handled. It was a teachable moment for me, which is to say that you have to own your size in those moments.

It actually turned out to be something positive. [Cinematographer] John Toll said to me something that Conrad Hall said to him, which is, “You only get to make this movie once. That’s true for every shot. It’s true for every day, and you’re going to live with it.” My job at certain times has been to save the studio from themselves. I’ve encountered the studio having even more anxiety about the money going out or the risk that they’re taking. And there are people who believe in the story, they believe in the script and the actors and you. You have to finally say, “I’ve got this.”

Would your career, the range of movies, some historic with strong messages, be impossible now?

I hate to think that’s true. People are going to have to invent ways, still, to do the things that they care about and that are personal and meaningful to them. Even now, seeing a certain fatigue about a comic-book universe in the culture, I like to hope that these things can be cyclical. Scale is necessary sometimes because it’s part of the palette that gives verisimilitude to the story. There’s a way that CG and some of the new technologies might be able to do something that that we did in a more real-time, real-scale way, like the German television show “Babylon Berlin.” It aspired to be a complex story about the rise of Nazism. That was a different way to skin that cat.

SOURCE: IndieWire