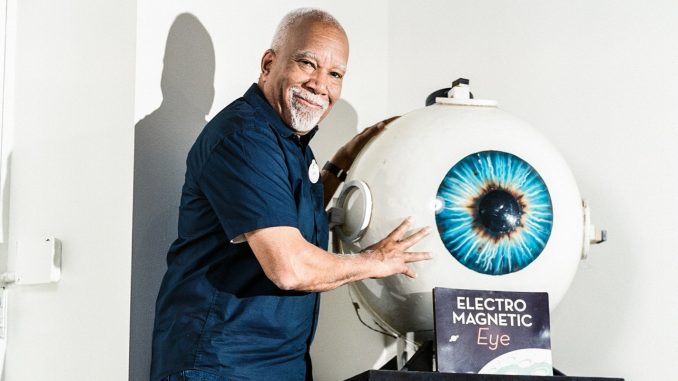

Lanny Smoot builds lightsabers for a living. No, not like the ones kids used to create with flashlights and plastic tubes—realistic extendable ones, with penumbral edges and laser-blocking abilities. Like an actual Jedi. He’s whipped up giant electromagnetic eyes, too, as well as an omnidirectional HoloTile Floor, which adapts to user movement and—like its spiritual parent, the Star Trek Holodeck—anticipates a world in which users can slap on an AR/VR headset and climb mountains or run marathons without leaving a single room.

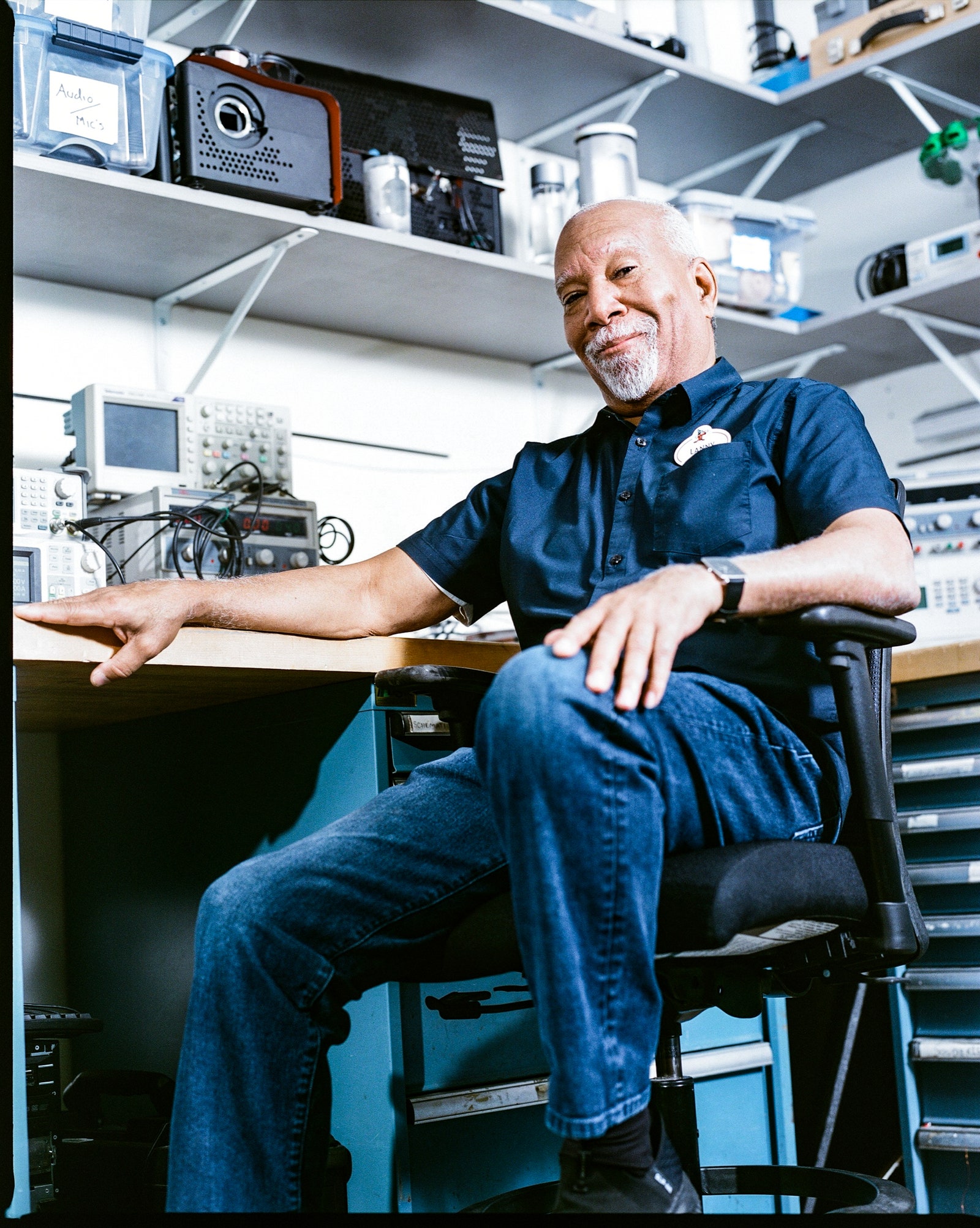

Building gadgets normally cooked up by Star Wars directors or visual effects supervisors is Smoot’s whole deal. A research fellow at Disney, his job involves a lot of making the science and technology behind Imagineers’ ideas actually work. Smoot, who began his career at Bell Labs, holds more patents than anyone at Disney—106 right now, with a few more “in the oven,” he says. He has been with the company for over 25 years and is only the second Disney employee ever inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

“I thought I was the first,” Smoot says, perched near a unicycle in his otherwise unassuming office on the Disney campus in Burbank, “but when someone told me I was the second, I immediately started thinking of colleagues who are very competitive, like, ‘Oh, it could be this one, it could be that one.’”

Later, he found out who beat him to the honor: Walt Disney.

Since its inception in 1952, Walt Disney Imagineering has been behind the launch of 12 theme parks, a planned community in Florida, five cruise ships, and dozens of resort hotels, shopping experiences, sports facilities, and entertainment venues—including some on Disney’s private island in the Bahamas. Responsible for everything from architecture to lighting to graphic design, the company’s Imagineers believe in not just creating new attractions, but also doing what Disney himself called “plussing”—constantly upgrading and innovating around the company’s existing attractions. Disney’s filmmakers build worlds that fans can watch onscreen; the research team builds in-canon worlds where they can avoid sunburn while sucking down blue milk and waiting to pilot the Millennium Falcon.

While different branches of Imagineering might use bakery smells to entice guests into Main Street eateries or employ forced perspective to make the the Magic Kingdom’s Cinderella Castle appear taller than it actually is, at Disney Research, Smoot’s department, Imagineers use science and engineering to push the boundaries of the company’s parks and attractions. They’ve created a “Stuntronic” Spider-Man capable of flipping through the air above the Avengers campus, and they’ve put riders on a swivel with the invention of the Omnicoaster system, which can rotate guests 360 degrees and launch them backwards, like on Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind. They also developed BB-8, creating a functional droid that could adorably coast around both movie sets and Disneyland’s Galaxy’s Edge.

Amongst all those brilliant minds, Smoot stands alone. As the only research fellow in Disney’s history, he’s held in high regard at the company. Doug Fidaleo, the director of the Disney Research Lab, says “Lanny embodies the purest spirit of imagineering, and with infectious optimism, creates unimaginable new realities that inspire the world.” Disney patent attorney Stuart Langley refers to Smoot as one of the most prolific Black inventors in American history. That orange orbicular droid the company was looking for? Smoot designed the drive system. Did Madame Leota’s floating head scare the crap out of you in the Haunted Mansion? Consider yourself delighted by his ingenuity.

Smoot’s love of all things electrical began about 58 years ago, when his dad—an “itinerant inventor” with a high school education—brought a battery, a bell, a light bulb, and some wire into their Brownsville, Brooklyn home. He showed his son how to wire a circuit and, “once he got the bell to ring and the lamp to light,” Smoot says, “it lit up my entire career.”

There weren’t a lot of Black engineers to look up to in his neighborhood, but Smoot says he grew to admire characters like Mission: Impossible’s Barney Collier, who could put together the show’s gadgets and hold his own in hand-to-hand combat. In junior high, a counselor steered him toward Brooklyn Technical High School and when it came time to apply to colleges, he got into every one tried for, from MIT to Columbia. He just couldn’t pay for them.

Somehow, though, Smoot’s name got to a recruiter at Bell Labs (at the time the most preeminent research facility in the world) who told him that they’d pay for his college and give him a summer job, as well as eventually pay for his master’s degree. Smoot agreed, and eventually joined Bell’s technical staff. There, he invented some of the first widely used fiber optic transmission systems, as well as circuits that helped network pay phones together.

In the ‘90s, Smoot says he developed an interest in people at home being able to control what they were seeing at sporting events. His resulting invention, the Electronic Panning Camera, allowed viewers to zoom around on whatever they were watching and made quite a splash when it debuted at the annual National Association of Broadcasters meeting in Las Vegas. That’s where Disney approached Smoot, asking to rent the system for a new project they cagily explained was about looking at animals “down in a pit.” (It was really for the company’s new Animal Kingdom park, and Smoot’s cameras were used to help staff and visitors keep track of elephants and zebras traversing the faux-savannah.)

Smoot’s meeting with Disney proved indicative. R&D at the company often takes the form of a black-box operation. Imagineers may know what they’re working on, but revealing too much kills the magic, so the public only ever sees their work in parks or cruise ships. Documentaries like The Imagineering Story offer insights (the basketball court under the Matterhorn is real), but they can feel like curated curtain-raisers. What Disney Imagineers actually do often remains a mystery to most people. “I don’t think it necessarily helps them as much as they maybe think it does,” Todd Martens, who covers Disney and its parks for the Los Angeles Times, says of the secrecy. “When you get off of the Haunted Mansion attraction, you always hear people talking about how the illusions worked. That makes you want to go in again, because then you get a sense of what’s really involved in making it.”

A job offer came shortly after Smoot met with Disney reps in Vegas, and soon he was running the company’s research site on Long Island. A move to Southern California with the rest of his group came in August of 2000, and now he’s spent decades building contraptions and solving tough technical questions for the company’s parks and resorts department.

While Smoot is technically a Disney Imagineer, he doesn’t identify as a creative person. Or, at least, not creative in the same way as the company’s artists, sculptors, and architects. “Back when I worked at Bell, I was an engineer and my boss was an engineer and the president of the company was an engineer,” he says. “We were very good at what we did and we made all sorts of things, but how they looked wasn’t important.” At Disney, the aesthetics and engineering both have to be impeccable. “I can draw a picture so I’m able to build something,” Smoot says, “but to make it look good, I call on my buddies.”

Smoot’s admirers might say that argument is a bit self-effacing. His accolades speak to the beauty in his work. “Whether they’re doing very hard science or engineering or working in some other technology, [inventors] see the elegance in what they’re doing and in how they’re presenting it to the world,” says Rini Paiva, the National Inventors Hall of Fame’s executive vice president of selection and recognition.

Smoot hand-picks his collaborators, and the projects he pursues. Bobby Bristow, an R&D Imagineer at Disney, says that in the eight or so years he’s worked with Smoot in what he calls the company’s “black ops” department, they’ve tackled “hundreds, if not thousands” of prototypes, many of which have never seen the light of day. “I’ll go home at night thinking about what we’re going to be doing the next day and how we’re going to approach and tackle it, and then when I come in the next morning, Lanny will be like, ‘No, no, I got this totally new idea when I was driving in’ and then we’ll end up working on some other crazy thing,” Bristow says.

At Disney, Smoot says, he’s also presented with all manner of technical challenges, thanks in part to the company’s wide-reaching scope. “I can wake up in the morning and start designing something that’s going into a cruise ship, and in the afternoon I’m working on something that’s going into Disneyland,” he says. “Three days later, someone will come to me with an issue that has to do with how our movies are made.”

Though ideas at Disney aren’t always developed in a linear fashion—a prototype of an invention might be started years before the company finds the place to put it into action, or an idea for something artistically cool might germinate for a bit before Research figures out the technology—Smoot has worked on a few things with a hard deadline, including the lightsabers for the Star Wars Launch Bay in 2015 and the Galactic Starcruiser in 2022.

While one could argue that not everything Disney makes is pure, inspirational magic, Smoot designs everything he works on to either entertain or spark joy. “There are engineers that have to work on things that can hurt people or that aren’t necessarily that good, and that’s never something I have to worry about,” Smoot says. Instead, he jokes, he just concerns himself with how Madame Leota will “float” through her seance room every few minutes for years on end. (He also had a hand in the operation of the Haunted Mansion’s stretching paintings, which were refurbished a few years back.)

Citing Arthur C. Clarke’s third law that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” Smoot says part of his work is about conveying a smooth and perfect sheen of surprise. When parents take their kids to a Disney park, they want those kids to have the same experience they did, even if all of the tech has been replaced.

Smoot points to Madame Leota as an example. Online, people had all kinds of theories about how Disney made the Haunted Mansion character fly—proof that Smoot’s tricks worked. “I read some descriptions from people who loved it and how they thought it worked, and without going into too much detail, I’ll say they were completely wrong and completely simplistic,” he says. “That’s when I said, ‘OK, yeah, what we did was good.’”

It’s this kind of impact that moves Smoot’s work beyond the realm of cool gadgetry. Paiva says that “when we look at potential inductees, we’re looking for inventors who have US patents that cover their work, which certainly Lanny has, but beyond that, we’re looking for inventors whose work has made societal, economic, and cultural impact.”

While Smoot’s Disney career has certainly wowed and enriched the lives of park goers and cruise ship passengers over the years, his work on teleconferencing at Bell was also an important factor into his induction, as was his work with aspiring young inventors.

“I’ve become a bit of a role model for young Black kids and people of color and women who have been looked over or not been in the room where things are done,” Smoot says. “I came from Brownsville, and I didn’t have a lot of money. Even today, I am one of the most thrifty people when it comes to building things. Some people say, ‘I can’t start my work unless I have this much money,’ but I’m like, ‘OK, I have a broomstick and I can take the keyboard apart…’”

Lonnie Johnson—a Black inventor and engineer who made the Inventors Hall of Fame for his work as the inventor of the Super Soaker as well as for his ongoing interest in renewable energy technology—says that Smoot’s outreach is vital, particularly for kids of color. He grew up in the ‘60s, joined the Civil Rights movement, and worked on the Galileo mission for NASA. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory may sound far removed from Disneyland, but Johnson says the experiences of prejudice can often be the same. “Peoples’ expectations are not what they would expect from someone who looks different from the way you are,” Johnson says. STEM needs people like Smoot, he adds, because “our world would be better served if we had more engineers from all backgrounds.”

As every park from the Magic Kingdom to Universal Studios becomes a franchise-ful playland, the onus is on Disney to make its themed worlds more extravagant, and also more personalized, customized, interactive. Disney plans to invest $60 billion in the growth of its parks and experiences over the next 10 years, and surely a chunk of that cash will be needed for new gadgets from Imagineers.

MagicBand+ wristbands, which allow people to access parks and unlock hotel rooms, aren’t actively used to track guests, per se, but one could imagine a world in which they’re used to hone someone’s ride experience—saving your high score or upping your level of difficulty on Toy Story Mania, for instance, or having the animatronic Tiana call out your name as you pass on the new Bayou Adventure. And while Disney’s Star Wars Galactic Starcruiser resort didn’t take off, immersive experiences like its Star Wars cantina have, indicating that fans want to put themselves into the world of their favorite movies.

There are new Frozen-themed lands coming to Hong Kong Disneyland, Walt Disney Studios Park in Paris, and Tokyo Disney Resort. A new Zootopia-themed land opened late last year at Shanghai Disney Resort. (Disney Research developed Duke Weaselton, a walking, jumping robot, for that one.) Disney Cruise Lines currently visits 94 ports in 40 countries with its five ships, and it plans to nearly double the line’s capacity in the next two years. There’s even some speculation that Disney might open a fifth theme park in Orlando, a suggestion that’s not out of the question given that the company currently holds about 1,000 acres of vacant land in the area—the equivalent of about seven Disneylands.

It’s easy to envision how Smoot’s HoloTile might integrate into those future Disney attractions. Users could walk at their own pace while traversing some virtual- or mixed-reality experience, or vehicles could spin and whirl through a trackless ride. A Disney Cruise passenger could groove through a dance fitness class on the tiles, or a park guest might be able to safely traverse an MCU-level clash on foot. Smoot even sees the tiles being used for staged productions, calling legendary choreographer and director Busby Berkeley’s immense, geometrically precise dance routines an inspiration.

The HoloTile has the potential to reach beyond the parks, as well. Gizmodo called it a “VR breakthrough,” while TechCrunch deemed it “an extremely clever and honestly quite elegant solution” to VR’s movement issues. While Disney typically doesn’t license out its technologies, Smoot says he’s already told his higher-ups that he thinks this invention could be big. He’s fielded some requests from interested collaborators. Whichever direction he goes, Smoot isn’t standing still.

SOURCE: Wired